When is the best time to view the Perseid meteor shower? Don’t wait until the peak nights to watch for the Perseid meteors. You can start watching a week or more before the peak nights of August 11-12 and 12-13, assuming you have a dark sky. The Perseid shower is known to rise gradually to a peak, then fall off rapidly afterwards. So as the nights pass in the week before the shower, the meteors will increase in number.

As a general rule, the Perseid meteors tend to be few and far between at nightfall and early evening. Yet, if fortune smiles upon you, you could catch an earthgrazer – a looooong, slow, colorful meteor traveling horizontally across the evening sky. Earthgrazer meteors are rare but most exciting and memorable, if you happen to spot one. Perseid earthgrazers can only appear at early to mid-evening, when the radiant point of the shower is close to the horizon.

As evening deepens into late night, and the meteor shower radiant climbs higher in the sky, more and more Perseid meteors streak the nighttime. The meteors don’t really start to pick up steam until after midnight, and usually don’t bombard the sky most abundantly until the wee hours before dawn. You may see 50 or so meteors per hour in a dark sky.

How to watch the Perseid meteor shower. You need no special equipment to enjoy this nighttime spectacle. You don’t even have to know the constellations. But you’ll definitely want to find a dark, open sky to fully enjoy the show. It also helps to be a night owl. Give yourself at least an hour of observing time, for these meteors in meteor showers come in spurts and are interspersed with lulls.

An open sky is essential because these meteors fly across the sky in many different directions and in front of numerous constellations. If you trace the paths of the Perseid meteors backward, you’d find they come from a point in front of the constellation Perseus. But once again, you don’t need to know Perseus or any other constellation to watch this or any meteor shower.

Enjoy the comfort of a reclining lawn chair and look upward in a dark sky, far away from pesky artificial lights. Remember, your eyes can take as long as twenty minutes to truly adapt to the darkness of night. So don’t rush the process. All good things come to those who wait.

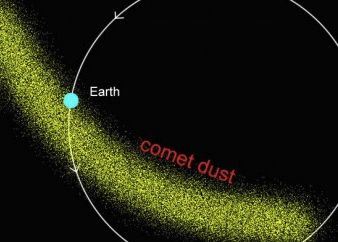

An

illustration from the 1872 Popular Science Monthly showing the

intersection of Earth’s orbit with the orbital path of Comet

Swift-Tuttle (Perseid meteoroid stream). Bits and pieces from this comet

burn up in the Earth’s upper atmosphere as Perseid meteors.

Comet Swift-Tuttle has a very eccentric – oblong – orbit that takes this comet outside the orbit of Pluto when farthest from the sun, and inside the Earth’s orbit when closest to the sun. It orbits the sun in a period of about 133 years. Every time this comet passes through the inner solar system, the sun warms and softens up the ices in the comet, causing it to release fresh comet material into its orbital stream. Comet Swift-Tuttle last reached perihelion – closest point to the sun – in December 1992 and will do so next in July 2126.

Although the Perseid meteor shower gives us one of the more reliable productions of the year, the ins and outs of any meteor shower cannot be known with absolute certainty. Forecasting the time and intensity of any meteor shower’s peak – or multiple peaks – is akin to predicting the outcome of a sporting event. There’s always the element of surprise and uncertainty. Depending on the year, the shower can exceed, or fall shy, of expectation.

The swift-moving and often bright Perseid meteors frequently leave persistent trains – ionized gas trails lasting for a few moments after the meteor has already gone. Watch for these meteors to streak the nighttime in front of the age-old, lore-laden constellations from late night until dawn as we approach the second weekend in August. The Perseids should put out a few dozen meteors per hour in the wee hours before dawn on the nights of August 10-11, 11-12 and 12-13.

The

constellation Cassiopeia points out the Douuble Cluster in northern tip

of the constellation Perseus. Faintly visible to the unaided eye on a

dark night, it’s better viewed with an optical aid. The Double Cluster

nearly marks the radiant of the Perseid meteor shower. Photo credit: madmiked

However, this is a chance alignment of the meteor shower radiant with the constellation Perseus. The stars in Perseus are light-years distant while these meteors burn up about 100 kilometers (60 miles) above the Earth’s surface. If any meteor survives its fiery plunge to hit the ground intact, the remaining portion is called a meteorite. Few – if any – meteors in meteor showers become meteorites, however, because of the flimsy nature of comet debris. Most meteorites are the remains of asteroids.

In ancient Greek star lore, Perseus is the son of the god Zeus and the mortal Danae. It is said that the Perseid shower commemorates the time when Zeus visited Danae, the mother of Perseus, in a shower of gold.

In our day and age of expanded artificial lighting, fewer and fewer people have actually seen the wonders of an inky black night sky. Why not make a date with the Perseid meteor shower this year and witness one of nature’s most remarkable sky shows?

Simply find a dark, open sky, enjoy the comfort of a reclining lawn chair and make a night of it!

Bottom line: No matter where you live worldwide, the 2013 Perseid meteor shower will probably be at its best on the nights of August 11-12 and/or August 12-13. Before dawn viewing is best. From northerly latitudes, you often see 50 or more meteors per hour, and from southerly latitudes in the Southern Hemisphere, perhaps you’ll see about one-third that many meteors.